Capital

Bull, Bear, Or Indifferent, It's Time To Game Out Housing Scenarios

Bullish signals flash green, while bearish noise ups the volume to an unholy din. Who's the contrarian? More importantly, who's early, late, and right?

Five years ago this month, Michael Batnick director of Research at Ritholtz Wealth Management LLC. and host of the Irrelevant Investor site, wrote about contrarians. He led off by laying out three buckets of contrarians, and his commentary strikes a chord now as housing bull and bear, signal and noise speculation surges on where housing's economic cycle is heading, and what that means for market-rate single-family and multifamily businesses.

- Early

- Late

- Right

For good measure, he added a fourth type, the knee-jerk contrarian. People who self-anoint as such, as Batnick notes, find a way to "always take the other side."

A friend in the business shared a link to Collaborative Fund partner and author Morgan Housel's "How people think."

If you read 240 words per minute, Housel's 17-item manifesto – which you'll find compelling – will take upwards of a half-hour. These days, that's a commitment, which Housel – who wrote the best-selling The Psychology of Money – acknowledges straight off.

It’s a long post, but each point can be read individually. Skip the ones you don’t agree with and reread the ones you do – that itself is a common way people think.

You may be able to get through almost 6,800 words in less than a half hour. Odds are, however, that you'll spend more time with Housel's masterpiece than that, re-reading.

Gem Number 4, for instance, has the heading: "We are extrapolating machines in a world where nothing too good or too bad lasts indefinitely."

Housel's expansion on this heading hits home, literally, at a moment of crazy volatility and uncertainty. He writes:

When you’re in the middle of a powerful trend it’s difficult to imagine a force strong enough to turn things the other way.

What we tend to miss is that what turns trends around usually isn’t an outside force. It’s when a subtle side effect of that trend erodes what made it powerful to begin with.

When there are no recessions, people get confident. When they get confident they take risks. When they take risks, you get recessions.

When markets never crash, valuations go up. When valuations go up, markets are prone to crash.

When there’s a crisis, people get motivated. When they get motivated they frantically solve problems. When they solve problems crises tend to end.

Good times plant the seeds of their destruction through complacency and leverage, and bad times plant the seeds of their turnaround through opportunity and panic-driven problem-solving.

We know that in hindsight. It’s almost always true, almost everywhere.

But we tend to only know it in hindsight because we are extrapolating machines, and drawing straight lines when forecasting is easier than imagining how people might adapt and change their behavior.

When alcohol from fermentation reaches a certain point it kills the yeast that made it in the first place. Most powerful trends end the same way. And that kind of force isn’t intuitive, requiring you to consider not just how a trend impacts people, but how that impact will change people’s behavior in a way that could end the trend.

Pair that insight Michael Batnick's take on contrarians.

It’s easy to be a contrarian, to think that you see something that the rest of the world is blind to. But it’s hard to be right.

Us mere mortals – ones who don't self-identify as contrarian for the sake of argument or a "scoop" – dwell now in a limbo of staying tuned, listening. And preparing, to the degree we can, for more to be revealed, to ensure business fitness, come what may.

The context here is of a prevailing bullish outlook among market-rate homebuilding and development companies based on crystal clear fundamental current conditions of demand and supply. One of the most compelling data points illustrating the imbalance comes from National Association of Home Builders chief economist Robert Dietz, who notes, that per 10 million US population, builders and developers produced just 21,288 starts on average during the decade from 2010 to 2019, roughly half or less than any prior decade on record.

Toll Brothers ceo Doug Yearley articulates the view in this piece by Andrew Barry in Barrons, widely embraced as the investment, strategic, and operational green light for 2022 and beyond, despite headwinds that have blown up to gale force levels. Barry's piece, "Why the Home Builders Are the Cheapest Stocks Around," quotes Yearley from a statement he made in Toll's Q1 2022 earnings release:

This market is being propelled by strong demographics, the substantial imbalance between the tight supply of homes and continued pent-up demand, growing equity in existing homes, migration trends, and the greater appreciation for home,” he said then. “We believe these long-term tailwinds will continue to support demand for new homes well into the future. With our significant and well-located land holdings and our unique niche in the luxury market, we are well positioned for continued growth.”

Contrarians, then – or those with a more bearish view of the outlook – hold that Yearley's view, and that of most of the industry's best, brightest, most-plugged-in, etc., contends that supply constraints pose bigger, longer-lasting challenges and risks than any of the forces that could alter consumer household demand.

So, an observation from the vantage point of "staying tuned, listening, and preparing for conditions that will one-day pronounce bearish contrarians early, late, right, or altogether off-base.

Observation one applies to those Treasury yield spreads and what their compression or inversion may foretell. It's just plain healthy risk assessment to game out best, medium, and worst-case scenarios should the economy pivot to recession as a result of the Fed's removal of punch bowl supports [Financial Times gift link] as it dials back its balance sheet and raises the cost of money.

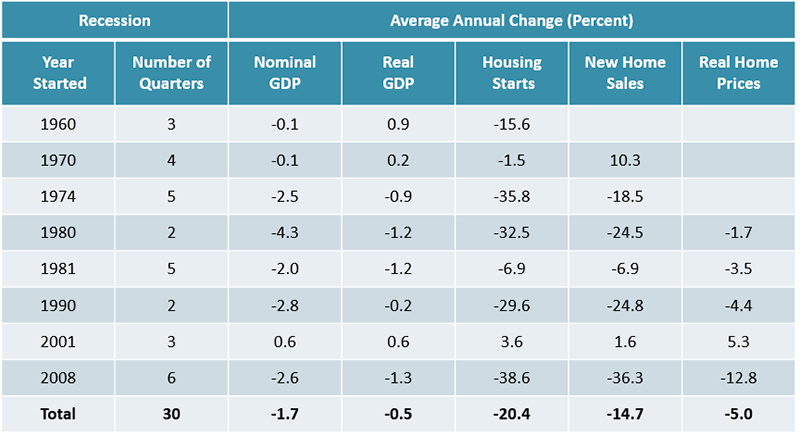

A Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies analysis by senior researcher Alexander Hermann in April 2020 – in the earliest stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, prior to the impact of Fed, Treasury, and Congressional financial rescue strategies – gives a glimpse at the impacts to housing activity in economic Recessions.

Demographics or not, here's what can go on if the economy weakens in the months ahead, tying directly to Housel's insight above, "When there are no recessions, people get confident. When they get confident they take risks. When they take risks, you get recessions":

According to our tabulations of data from the National Bureau of Economic Research, there have been eight recessions since 1960. From peak to trough, these recessions have lasted nearly four quarters on average. The longest, during the Great Recession, lasted six quarters. Declines in housing production and new home sales occurred in all prior recessions. In data going back to 1960, year-over-year housing starts fell by an average of 20 percent in quarters with a recession (Figure 1). In data going back to 1970, new home sales declined 15 percent on average during recessions. Likewise, in recessions since 1980, real home prices declined 5 percent year-over-year, on average, with annual declines in all but one recession (the recession beginning in 2001).

Hermann's research charts out as follows, an evidence-based analysis of the effects of recessions on housing activity:

Housing starts in February 2009, we'll be hesitant to recall, bottomed at 466,000.

So, it may be time now to ask yourself a question. "Do I feel lucky?"

Join the conversation

MORE IN Capital

Timing Demand: Why Investors Choose To Buy Apartments Vs. Building

A construction slowdown today is setting up an undersupply tomorrow. Opportunistic, patient investors are already pivoting to seize future market growth catalysts.

Little Deal ... Big, Timely Product Pivot: Lokal’s Capital Play

A $12M facility fuels Lokal Homes’ swift shift into higher-margin homes and a smarter land strategy in a tough market.

Land, Capital, And Control — A New Playbook In Homebuilding

Five Point Holdings’ acquisition of a controlling stake in Hearthstone points to the direction of homebuilding strategy: toward lighter land positions, more agile capital flows, and a far more disciplined focus on vertical construction, consumer targeting, and time-to-market velocity.