Leadership

For Bumpy Months Ahead, Doing More With Less Is Not An Option

From Q4 '22 through the end of '23, homebuilders that ramped up operations will now have to reset resources to an evolving, indefinite new reality ... a period that may require an focused 'what-not-to-do' list.

This past Spring, market conditions for homebuilders and their partners of every stripe and size crossed a Rubicon. Big challenges of the nature businesses prefer to have – i.e. hustling like hell to meet surging demand profitably – were swapped out, virtually overnight, with challenges anybody in their right mind would do almost anything to avoid. Namely, a sudden shrinkage in customer demand.

Is "sudden" an unfairly strong way to describe the tipping point?

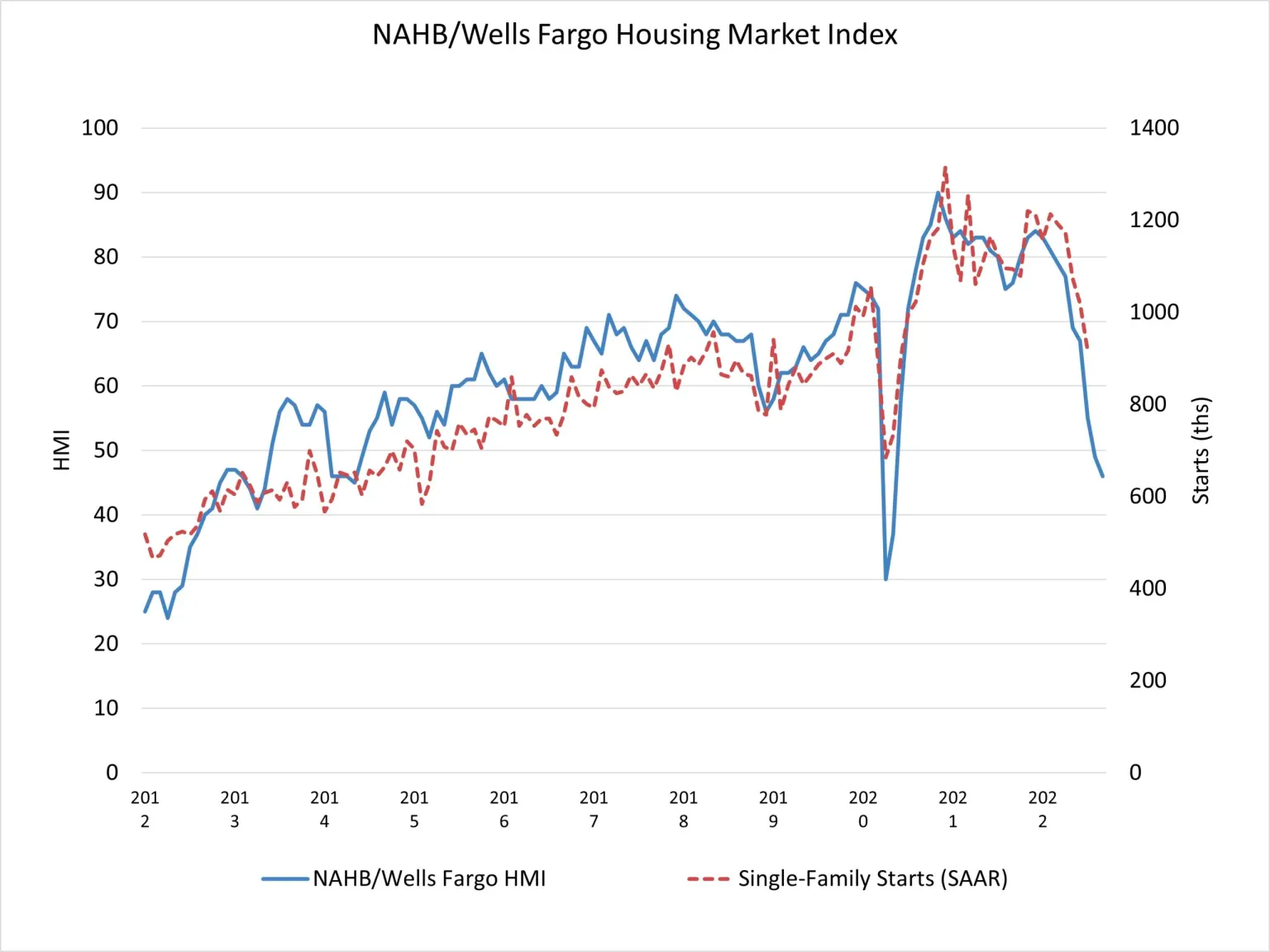

This morning's release of September data for the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB)/Wells Fargo Housing Market Index (HMI) is a case-study in "suddenness" for a housing market turn.

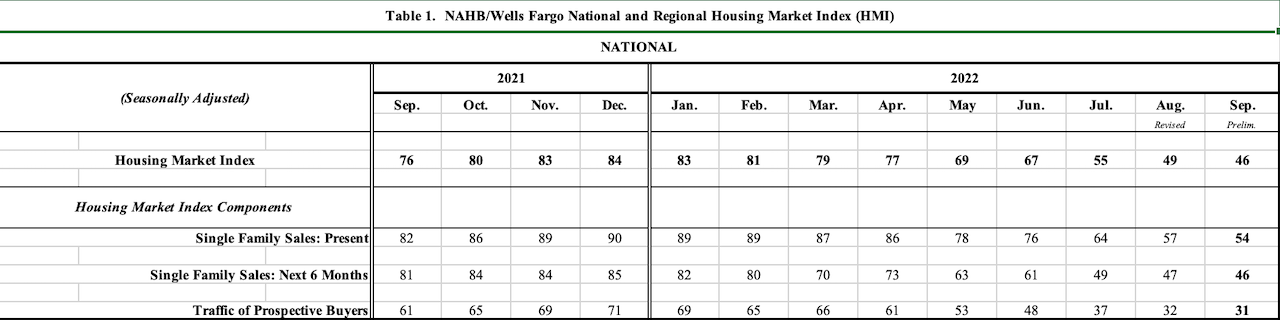

The data points, numerically, bear out the level of change – where a value above 50 means that more builders are positive, and below 50 means more builders are negative – from January through September.

But the numbers alone don't tell the full story of how profound a pivot has taken place. The steepness of change – from high-flying to crashing – comes through better in the visualization of the data points across the 9-month time period here:

What may be in question until further notice – complicated by typical seasonal slowing versus a atypical levels of urgency among homebuilders to try to clear some large portion of under-construction, standing and spec home inventory – is whether the rate of deterioration in the overall market, as well as the continued dispersion of weakness into more and more markets and submarkets have run to their peak rates of change or not.

What has been the case regarding the fast spread of the correction is that what started as trouble in a few of the frothier markets as an exception has now flipped to where there's a marked series of speedbumps in most markets, with a vastly smaller number of them holding up well so far.

As the NAHB notes, one of every four homebuilders cut home prices at the time of the lasted HMI survey, a number that probably under-reports a survey universe predominantly reliant on bank lending construction and project finance as well as for land acquisition and development.

To keep bank loan covenants from tripping, builders – especially privately-held, bank-financed ones – have to keep closing their backlog and spec homes on a predictable, programmatic pace-basis, both to keep cash flow where it needs to be, and to stay within their sworn-affidavit loan covenant parameters every month.

This boils down to a game of pricing "chicken," one that typically involves hesitance and tiny, reluctant pricing moves, until a capitulation event occurs. One executive level homebuilding and development strategist we talk with says:

Cash flow is king…seeing a lot of builders hesitant to drop prices enough to keep up a moderate pace which will cause much more pain down the road….incentives won’t be enough to get through it."

Another highly-placed executive comments:

Right now, most private builders' fate is in the hands of the publics, especially Lennar and Horton," this executive says. "My own belief is that neither of those guys will tolerate a reduction in their sales of more than 20-30% next year, and probably closer to 20%. I think they'd rather tell Wall Street that margins fell by half, than volume fell by 40%. So they will do what it takes to make sales, and will create cash flow no matter what, given no covenant unsecured debt. And if what it takes to that is severe discounts, they will do so. And privates will have no option but to follow and all cash will go to payoff secured bank loan. Land bankers, equity shops, private builders, all are going to watch their fate controlled by the big guys."

When it comes to making those sudden, almost irrationally steep price cuts early on in a correction, the rule of "he who cuts first cuts least" reflects received wisdom through the ages of housing cycle and who survived them, who came out of them stronger, and who did not make it through.

The particular challenges of how to keep driving backlog units through to settlement, fight cancellations, navigate the trickiest of mortgage lending backdrops, deal with the stubborn aftershock effects of supply chain chokeholds, and a market dynamic that is producing specs where there were none earlier, ... all head inevitably to a "doing more with less" stretch.

"Doing more with less," of course, is a thinly veiled euphemism in most cases for businesses cutting back on resources when sales volumes and revenues are heading downward, as they are now for many homebuilders and their partners.

"Doing more with less" can, of course, bring out the best in some firms. They're the ones that look at products, practices, and processes not as snapshots of value that remains static, but as opportunity-areas for improvement, for ideas, etc.

As leaders, the challenge to cut ASPs and flow those price reductions through the business with as little impact as possible on margins – although, as our executive advisor notes above, the biggest players will trade off margins in favor of sustaining unit volume first, and then beg forgiveness with Wall Street later, when they're able to leverage those unit volumes into market share clout to reduce overheads and rebuild margins later – is a matter of cutting wisely and getting fewer resources to produce as much.

Effectively, most homebuilding organizations – because they don't tend to be bloated in the first place – now have, what "Subtract: The Untapped Science of Less" author Leidy Klotz calls a "time famine" challenge.

In that context, you're leading organizations that – given the number of human resources you have – have more to do than they can excel at right now, when exactly what they need to do is excel. As homebuilding business leaders, the "stop-doing" list is right up there with the "to-do" priorities list, and the thing is, it's not enough to tell your team, "think of things you need to stop doing, and remove them from your priorities." We know how that works.

A stop-doing list might mean eliminating a meeting, which can put time back in a team member's schedule, and allow them to be more productive. However, the value that initial meeting schedule had can not be simply left by the wayside – a smarter, more streamlined way of accomplishing what would occur in that meeting needs to be part of the "stop-doing" list.

- Products – stop-doing what today's would-be home purchaser doesn't declare is valuable in their home and property.

- Processes – Subtract friction and time-sucks from your team's project stream so that their sense of agency and accountability in the process increases inversely with any waste of time not being effective.

- Practices – weed out the ones that are company artifacts that are "the way we've always done things" if and when they're not vitally important to matching up your value offerings with customers who'll value them.

When cash is king, as one of our executive strategists asserts is the way to characterize builders' challenge of the moment, it's no time for sacred cows or pet projects. Cutting prices unambiguously means cutting more than that, and a leader's job right now is to work alongside managers to recognize and solve holistically for what to stop doing.

Join the conversation

MORE IN Leadership

Eastwood Homes, Napolitano Unite In Culture-First M&A Deal

In a rare private-to-private M&A deal, Eastwood Homes acquires Virginia’s Napolitano Homes—uniting two family-founded builders in a move that blends culture, strategic market expansion, product synergy, and generational transition.

Fire-Ready Future Forward: KB Home Builds Hardened Homes At Scale

Escondido, CA-area’s Dixon Trail becomes the nation’s first IBHS-certified Wildfire Prepared Neighborhood—fusing resilience, affordability, and innovation into a new model for community design.

KB Home Guidance Cut Bodes Sharper Sector Challenges Ahead

In a reflection of broader market tensions, KB Home — following on an earlier lowered guidance from Lennar — drastically revises its 2025 outlook downward amid weakening consumer confidence and escalating costs.