Products

'Living With' The Supply Chain Crisis May Be A Last Best Option

For construction supply woes, sellers and buyers choose to go-it-alone and keep close-to-the-vest at their own peril. Transparency and trust work as tools to learn to 'live with' supply disruption.

Two critical forces won't behave as people want them to, at all.

Covid and the global supply chain, including the supply of 18,000 piece-level materials and products needed to assemble a new home.

Some view the misbehavior as defying prediction. Others looked, starting last Spring and flowing through this past late-Winter, and predicted exactly what's going on for both – a fourth wave of Covid cases and deaths, and a massively disrupted building materials and products supply chain that will blow well past the end of 2021 at least into the middle part of 2022.

Some, according to this piece in the New York Times by Peter S. Goodman and Keith Bradsher, believe that it's well past time any construction manager or purchasing agent or superintendent or community director or division president should be surprised by any newly emerging breakage in the building lifecycle.

It's also past time to begin to factor in, price in, manage to, and plan around the reality of a disrupted – broken – supply chain. There are sweeping implications leaders must begin to pivot on, and dig deep into to create pathways people can get and align with. Among those implications:

- "transitory" inflation may be sticking around longer than expected and stressing budget and operational forecasts.

- Outcomes modeled 12 months ago, or even 6 months ago, may be unachievable, with a knock-on effect to accountability, management goals, and measures of skill and direction.

- Relationships founded on contractual and transactional metrics will need to absorb variance, re-terming, and a bottom-line alignment of values as opposed to strict, literal agreement language as binding.

It should, by now, expected that this is the state of things to learn to live with.

Factories around the world are limiting operations — despite powerful demand for their wares — because they cannot buy metal parts, plastics and raw materials. Construction companies are paying more for paint, lumber and hardware, while waiting weeks and sometimes months to receive what they need.

Window delivery times now extend from 24 to 27 weeks from the time of order, and can not be surge-ordered nor ordered on spec from basically a handful of window manufacturers who produce and distribute the lion's share of windows – 15 or so to the average 2,200 sq. ft. new home. For drywall, paint, stucco, all materials builders need to progress their started homes through the cycle, the delays daily feed directly into a massive choke point. The Times article goes on:

There is no end in sight,” said Alan Holland, chief executive of Keelvar, a company based in Cork, Ireland, that makes software used to manage supply chains. “Everybody should be assuming we are going to have an extended period of disruptions.”

It's all well and good to make a broad statement like that, and it may well be true. But what, truly and exactly, does it mean when "everybody should be assuming we are going to have an extended period of disruptions."

It's the same challenge as the one that sounds like, "everybody should be assuming we are going to have to learn to live with Covid."

Easier said than done.

And for builders, whose far-upfront and heavily front-loaded investment in real estate is essentially an hour-glass whose window to either gain big or lose big on their land deals depends on turning over the inventory in a timely way at a predicted level, this can get very expensive, very fast.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York's Liberty Street Economics researchers Victoria E. Agwam, Pablo D. Azar, and Kyra Frye studied the knock-on and spillover effects of Covid on both productivity and an ecosystem of supply chains that, together, weighed down the economy. They write here:

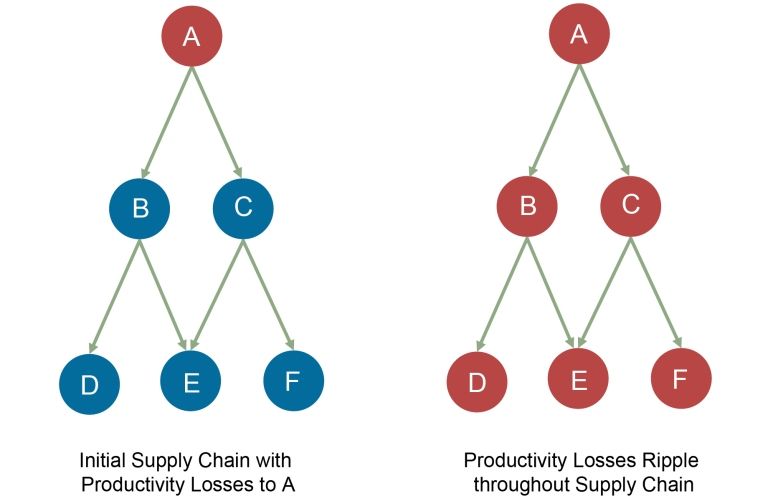

A productivity shock—such as the one induced by COVID-19—can ripple through the supply chain network. The introduction of a shock to industry “A” is represented with a red circle on the left-hand side. The transition from left to right, or from partially blue to all red, exemplifies how productivity losses to one industry can lead to similar losses in connected industries.

Accepting that supply disruption will be lasting, and may get worse – in terms of both material availability, timeliness, and cost – before it gets better stands as a very difficult pill to swallow, particularly in a business and manufacturing culture whose workaround to critical path and scheduling challenges tends to be to throw more money at the problem, or move past the critical path item and plan to come back to it later – even if the loss of sequence runs costs higher, and even potentially impacts quality.

It's a widely known fact that one of the last options many homebuilding organizations would resort to is exactly the option many supply chain strategists insist would be the best route.

Farida Ali, ceo and president of Dynamic Technology Solutions, writes:

In the current manufacturing environment — where no clear standards exist for what is and what is not acceptable supply chain risk — relationships need to be developed that define and formally align the interests of the purchaser and the supplier. Investment of time and resources are required to establish that type of high-level, non-transactional support from suppliers. Those relationships must also be based on trust, so that suppliers are comfortable sharing potentially negative information with customers.

For meaningful change to occur in the management of supply chain risks, the underlying dynamics of the company-supplier relationship need to shift to proactive “pushing” of critical information by suppliers to manufacturers and away from the reactive “pulling” of information from suppliers by manufacturers. Companies must expect all suppliers to have skin in the game and require them to identify and keep them informed of potential risks.

Fourth quarter of 2021 will be a tsunami of Extra Purchase Orders, Variance Purchase Orders, Field Purchase Orders.

Who's on the hook for them? Who takes the hit?

Is it the promised, up-to-now mightily handsome margins builders have been mapping into their year-end forecasts, albeit on fewer than anticipated completed sales?

Who's on the hook?

Is it the field supervisors, the local purchasing folks working their brains to come up with that day's five workaround solutions? Is it the division managers and presidents who'll take a hit to their bonuses for not making their numbers?

Will the pain spread across the enterprise line into relationships with vendors, showing up as punitive measures in light of Covid-related delays that triggered a daisy-chain of expensive work-arounds?

Trust and transparency. These go-to values are baseline options, good times or bad; especially bad. Trust and transparency will be the way to build back stronger and better and faster once things do ease up in the supply channel.

Join the conversation

MORE IN Products

How Precision Can Shave Time From Homebuilders' Build Cycle

Sales may be priority No. 1 right now. And that needs to be bolstered by virtually flawless operations. Boise Cascade’s SawTek gives builders speed, savings, and first-time-right quality when it matters most.

In Uncertain Times, Capability Investment Is A Survival Tool

Boise Cascade’s $140M mill improvements reflect a long-game commitment to builders under pressure from volatility, costs, and customer hesitation.

Margins Tighten, Value-Add Matters In Construction Supply

Even as overall construction supply revenues inch upward, Webb Analytics’ deep dive into the $600B pro channel reveals a shifting reality: declining unit volume, cautious outlooks, and strategic bright spots in value-added manufacturing and service partnerships.