Policy

What's Been Stalling The Future Of Building Is Not Construction

Construction and real estate are fused together, and real estate – with its politics, its environment, its neighbors, its stack of property stakeholders – is where the wheels of innovation and transformation grind slowly or not at all.

Can the construction industry be disrupted?

Author and Harvard Law School fellow Mark Erlich – or his Harvard Business Review editors – flirt with a maxim known as Betteridge's law of headlines. This law states:

Any headline that ends in a question mark can be answered by the word no."

We'd say flirt, because within the less than 2,000 words of Erlich's essay, he makes quite a strong case for why the answer is yes.

Exploring the question's ins and outs, Erlich concludes that transformative advances will come, but slowly and in different formats than those that have catapulted manufacturing and other industry sectors into their more-productive, more value-creating futures.

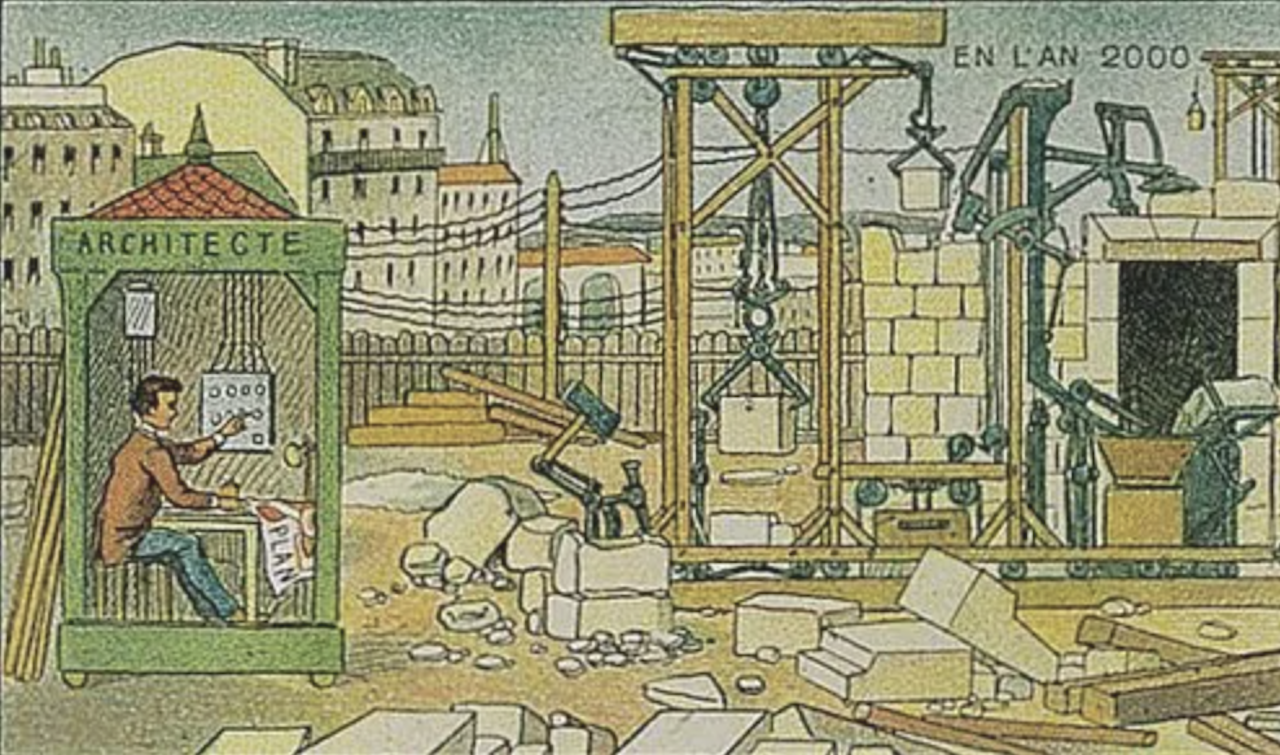

Erlich kicks off his exploration with a strong visual. He draws us to the work of a French illustrator named Villemard, who in 1910 made a series of uncannily predictive illustrations of a year 2000 future. They're worth a look, and not just for Villemard's illustration of an architect at a construction job-site imagined as a hardhat-and-human-free robotic "factory-in-the-field."

They call to mind another genius visionary, Leonardo da Vinci, some of whose 500-year-old Codex Atlanticus notebook leaves – "studies and sketches for paintings, works on mechanics, hydraulics, mathematics, astronomy as well as philosophical meditations and fables. It also has many inventions such as parachutes, war machineries and hydraulic pumps" – made a rare trip to the U.S., and are on display in Washington, D.C. through Aug. 20.

Whether it's Leonardo or Villemard who's the visionary brought into the conversation about construction's ripeness for disruption, the answer to the question "can it be disrupted?" is an unambiguous yes.

Will it, though?

That's another matter.

Ehrlic takes pains to explore "community of practice" inertial forces – decentralization and specialization among the 25-trade stack of construction crews and cadences and hand-offs across a 150 to 210-day build-cycle -- that have weighed heavily for decades against radical process improvement. He also delves into the problem of the dirt – the too-often unique demands of one building site versus all the others – as a show-stopper for the kind of repeatability that has made manufacturing and industrialization "modern." Erlich writes:

State-of the-art six-axis articulated robots may have transformed the auto industry, but their stationery character does not work on a construction site. A robot that is immobile and cannot adjust to the rough terrain and multi-story nature of a building project is functionally useless. Autonomous earth-moving machinery can dig out and prepare foundations. Robots can do simple layout. Drones can navigate job sites and record daily progress. Exoskeletons can relieve the burden of lifting heavy items and YouTube videos portray the wonders of 3D printing. Yet many of these advances remain novelty items, available only to a minority of firms that have the resources and inclination to experiment with equipment and systems that have not consistently been proven to be quality- or cost-effective."

Add to the balance sheet efficiencies of all this inefficiency – easily eliminated variable expenses of labor, materials, land, and other costs when the housing cycle slows, and expanded when mojo kicks back up – are economic disincentives to change, as Erlich notes:

Construction executives found simpler ways to cut labor costs through the misclassification of employees as independent contractors, cash compensation, and reduced wages and safety standards — all components of a successful crusade to undermine the union sector in many parts of the country. There is less incentive to buy robots to replace high-priced labor when the labor itself is not as pricey."

These well-appreciated factors thwart progress, and are a big part of why the potential for transformative disruption continues as just that, potential rather than reality.

There's an even more fundamental, simple and consequential an impediment to converting this potential into step-change improvement, productivity, efficiency, and profitability.

It's that construction and real estate are fused together, and real estate – with its politics, its environment, its neighbors, its stack of property stakeholders – is where the wheels of innovation and transformation grind slowly or not at all.

Think of the number of instances where, despite many yeas a single nay can derail development and construction deals that spread gain, limit pain, and expand attainability for more area people in need of ground-up housing options.

Construction technologies and processes – even were they to suck out 20% or 30% of input costs in start-to-completion build-cycles – won't ever transfer those efficiencies, those powers of innovation to bend the cost curve, if more, and more attainable, and more sustainable housing is exactly what neighbors and voters and jurisdictions don't want.

To alter that dynamic, property ownership and its taxation, valuation, and local political sway need a Leonardo- or Villemard-like re-imagining.

The question isn't "can the construction industry be disrupted?" because as Leonardo and Villemard illustrate, "if it can be imagined, it is."

The question that will impact whether that potential ever becomes reality is, "will the construction industry be disrupted?"

A lot of people would rather it not be, and that doesn't only mean established incumbent marketshare leaders. It means you and me.

MORE IN Policy

Can Ditching the Car Unlock Pent-Up Housing Demand?

A car-free lifestyle could help homebuyers afford more — and give developers a powerful new lever near transit hubs. It's part of a 'missing middle' solutions set.

California Breaks CEQA Barrier To Reignite Housing Production

Championed aggressively by Gov. Gavin Newsom, the historic environmental law reform unlocks the potential for infill housing—and could become a model for other high-barrier states.

Governor’s Veto Derails Connecticut Upzoning Push

State leaders aim to regroup for a fall special session after a housing bill faces resistance from local zoning defenders.