Land

We Engineered This Housing Crisis — It Didn’t Just Happen

Metro housing policy has become a self-defeating maze. The Builder's Daily contributor Scott Cox helps us with data, wisdom, and courage to map the math, myths, and real path forward.

The housing affordability crisis gripping the Denver MSA is not a failure of the free market. It’s not the result of greedy builders or an accident of economic fate.

It’s the output of a set of deliberate choices—decades in the making—and a refusal to take seriously the math of what it takes to build homes people can afford.

And Denver is just one face of a national pattern. From Portland to Phoenix, Austin to Atlanta, local, state, and federal housing policy interventions—often well-intentioned — are multiplying the very problem they claim and aim to solve.

Scott Cox, one of the smartest land and capital strategists in the U.S. homebuilding sector and a contributor to The Builder’s Daily, lays out the clearest roadmap we’ve seen of how we got here.

And how we keep digging the hole deeper.

In a presentation titled Choices Have Consequences, Cox pulls no punches. His argument is simple:

We are a result of our choices, not chance.”

The Numbers Don’t Lie

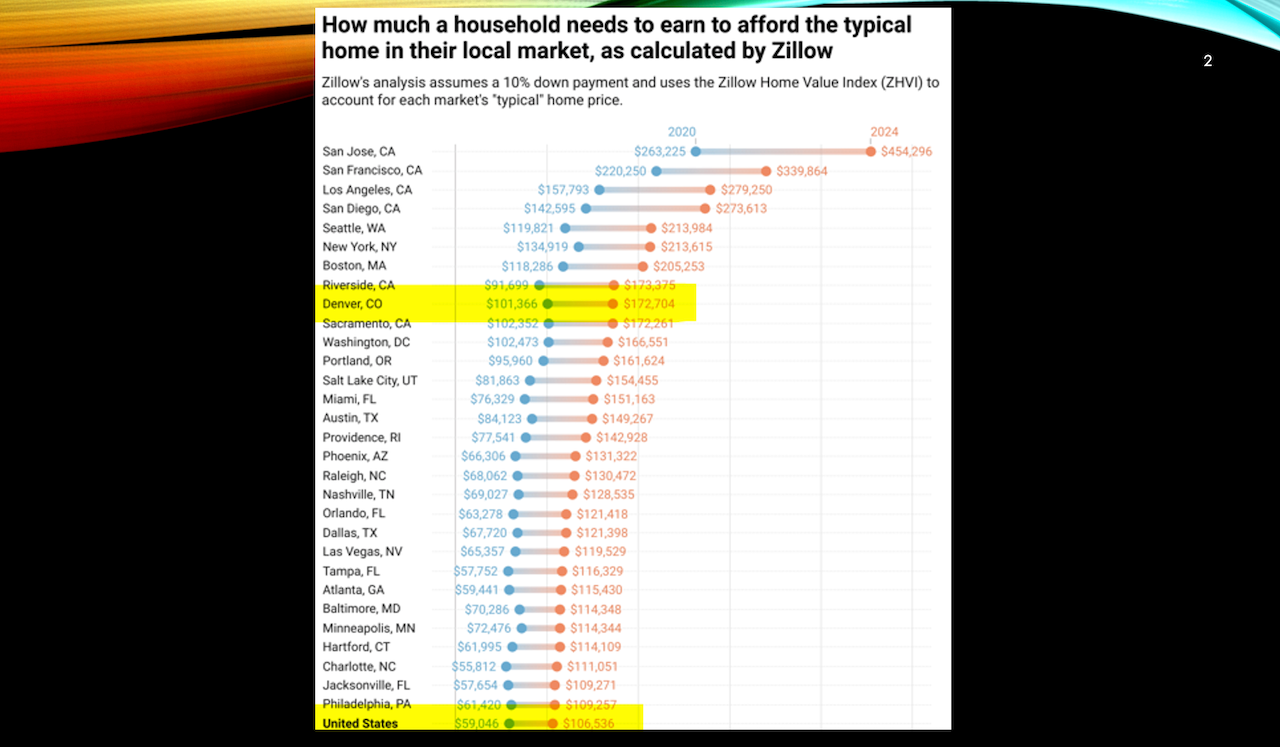

Start with the mismatch. Since 2010, the Denver MSA has added 32,000 jobs per year, but has averaged just 20,000 housing permits annually. That’s a deficit of 7,000 homes per year, every year, for over a decade.

The shortfall is even more glaring in single-family housing. Based on job growth and a balanced market assumption (a 2:1 job-to-SF ratio), the metro is 74,000 single-family homes short.

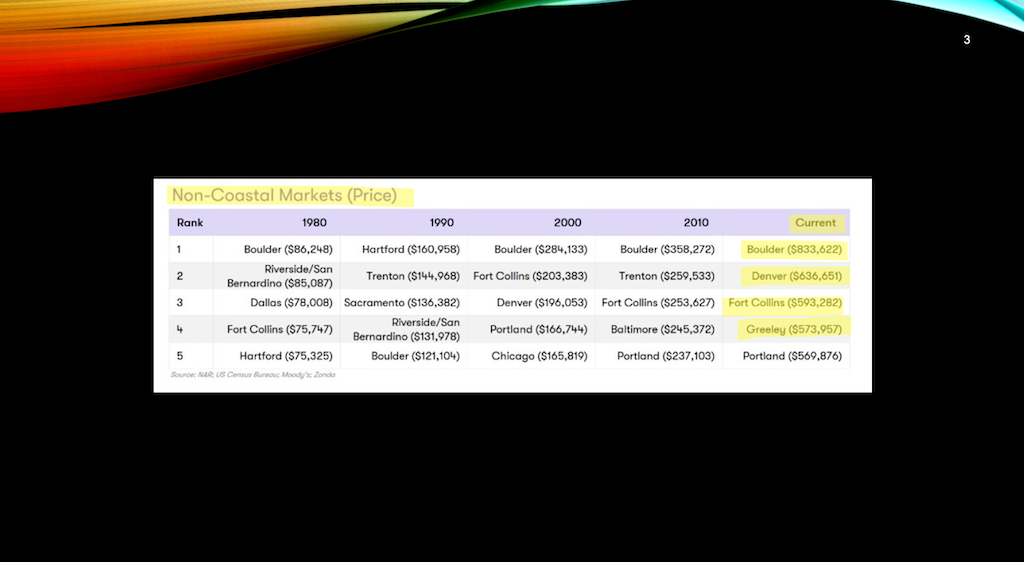

Single-family homes become a luxury good,” Cox writes. We’re doing everything California did to get in trouble—and trying the same failed solutions.”

Meanwhile, the stated demand hasn’t changed: 80% of the population still wants to own a single-family home. Denver’s homeownership rate has dropped to 64%, and it's heading south fast.

Scapegoats and Lazy Thinking

Cox dismantles the familiar narratives that get trotted out to explain the affordability crisis:

- "Builders make too much money.” But typical margins are 8–10%. “Taking 10% off the price wouldn’t fix our problems, even if it were possible.”

- “We’re building the wrong stuff.” Yet vacancy rates are historically low.

- “Public builders have too much market share.” They prioritize velocity over price. That’s not bad for affordability—it helps.

And the most persistent myth of all? Sprawl.

Cox argues that “sprawl” has become shorthand for “no suburban housing.” Yet Denver averages just 3.5 units per acre. Suburban builders typically seek 6–15 units per acre but often get rejected.

Why is building denser than existing cities called ‘sprawl’?”

We need small detached homes, duplexes, and townhomes. But our land-use regimes reject them outright or regulate them into impossibility.

The Math Nobody Cares To Do

The most striking aspect of Cox’s analysis is the math that no one else wants to tackle.

Let’s say we try to fix the shortage with subsidized affordable housing. Even with generous assumptions — $150,000 per unit in subsidy — it would cost $1 billion per year to fix the 7,000-unit annual shortfall.

Even if we found that money, and we will not,” Cox writes, “we still have to approve an extra 7,000 units a year. Or we are right back where we started.”

To catch up from the past 12 years, Denver would need $12 billion in subsidies.

Making expensive things more expensive isn’t a solution,” he adds, swiping at inclusionary zoning fees and added exactions.

Blueprint Denver — the city’s major housing plan — ran 348 pages. Not once, Cox points out, did it calculate how much land would be available under the new rules, what kinds of housing would be feasible, or how many affordable units might result.

We seem to be afraid of math.”

Root Causes: A System Destined to Fail

Cox identifies culprits. They are structural. Policy choices. And they span the country:

- Restrictive land use rules. “The approval process is lengthy, tortuous, and often random and capricious,” Cox writes. Codes are so complex that few projects are ever “by right.” Public input has become a veto.

- Ever-rising standards and codes. Net-zero mandates, sprinklers, and incremental climate add-ons pile on costs. But new homes only add 20,000 units a year to a metro with 1.2 million homes. “Focusing on taking the incremental 20K per year from very good to great is not the answer,” Cox says. Retrofitting the existing base is far more effective.

- Elimination of the bottom rungs of the housing ladder. Condos? Killed by construction defect litigation. Manufactured housing? Protected existing stock, but the new supply was blocked. Boarding houses and SROs? Forbidden. “We eliminated the bottom rungs on the housing ladder.”

- Broken litigation reform. Supposed fixes to construction defect law increase risk and cost. “Do we believe contractors are good at building apartments, but not condos?” Cox asks. “Then why do we see endless lawsuits over condos and not apartments?”

- Impact fees that penalize small homes. Because fees are per unit, not per square foot, they create a perverse incentive: build larger, more expensive homes to amortize the cost.

- Failure to build infrastructure at scale. “Developers should pay their way” really means that new home buyers should pay both to fix old problems and to build new infrastructure and additional capacity for the future. This is backwards, Cox argues. Infrastructure should be built by those with the lowest capital costs and the largest scale: local, regional, and state governments.

Einstein's Definition Of Insanity

Cox draws a straight line to California. Homeownership rates have plunged to 54% there. Median home prices are out of reach for most families.

Almost all our proposed solutions will result in for-rent, not for-sale housing,” he writes. And “single-family homes will be a luxury good that most of the public will not be able to afford.”

That’s not a warning. It’s a guarantee—if we stay on the current course.

What Would Help

Cox isn’t just diagnosing the disease. He prescribes remedies—pragmatic, cost-aware, politically thorny, but realistic:

- Build infrastructure with (local, regional, and state) public capital.

- Stop labeling every suburban proposal ‘sprawl.’

- Tie fees to house size, not unit count.

- Make 1,400-square-foot lots by right. Cox calls this “the best single land-use policy to create home ownership opportunities I’ve seen.”

- Simplify and broaden zoning categories.

- Stop treating local control as sacrosanct. Without shared obligations, we face a “prisoner’s dilemma.”

Above all, we must accept that creativity means tolerating the occasional bad outcome.

You can’t have a wide variety of solutions and like every single one,” Cox writes.

A Job for Leaders

Every homebuilding business leader knows: hope is not a strategy, and slogans are not solutions. We understand the challenges of acquiring land, securing entitlements, and delivering homes in today’s environment. But business leadership also means stepping into the broader conversation about what’s driving those difficulties—and having the courage to call out what’s broken.

This is the work Scott Cox has done. And it’s work we at The Builder’s Daily believe is essential. Because what’s happening in Denver isn’t just happening in Denver. The policy choices playing out across metro areas—from Virginia to Nevada—are variations on the same themes.

We’re not stuck. We’re just scared to change course. But change is the only way forward.

MORE IN Land

Texas Land, Texas Spirit: A Wake-up Call For Better Neighborhoods

Scott Finfer calls for a reinvention of how communities are built—away from formulaic lot counts and toward ecosystems rooted in landscape, design, and daily experience. His essay challenges developers to deliver neighborhoods that endure and reflect the best of the Texas spirit.

BTI’s Long-Game: Big Land Bets Amid Homebuilder Tactics Shifts

CIO Justin Onorato explains why developer BTI sees resilience in Florida, Texas, and Colorado markets, and how population dynamics shape its long-view strategy.

Land Risk Is Rising. So Is Homebuilder Blindness To It.

As homebuilders face volatile demand, rising input costs, and tighter capital controls, the risks of land missteps grow. Acres.com CEO Carter Malloy makes the case for a new class of competitive land intel—built to give builders visibility into what’s really happening before it’s too late.