Policy

Eviction Data: Biggest Toll On Blacks, Women, Vulnerable

A looming eviction crisis, coming amid market-rate boom, calls on housing's leaders and policymakers to work for solutions.

Second-quarter 2021 earnings among leading single-family enterprise and multifamily REIT strategic executives have been cause for jubilance. Housing's meteoric recovery from last Spring's abyss, and its resilience in the face of ongoing economic shocks and stresses reflect resolve, hard work, and courage.

Still, this profoundly sad tale-of-two-housing-realities moment starts a dark chapter for everybody whose livelihood springs from work producing homes and communities.

Wall Street back-flips at how great housing's doing on the one hand; evictions, and displaced families and individuals on the other. That's a dark chapter for housing, which as we note here, represents almost a full fifth of our economy today.

No one today knows just how many families, households, individuals – of the some 7 million who have fallen behind in their rents – will face eviction, now that federal bans and moratoria have expired and states are left to their own devices on extending further protections or not.

The issue is that the people at highest risk of the biggest, most damaging, and most lasting pain in this equation – just as market-rate enterprises are celebrating their financial and operational performance during a housing boom – are America's people of color, its female-headed households, its citizens who are financially or health-wise vulnerable, its communities who've forever and always taken the hardest hits in any economic era, good or bad.

Brookings Institution Metropolitan Policy Program researchers, Carl Romer, Andre M. Perry, and Kristen Broady, offer a deep data and literature dive into what's a reality for 30 million to 40 million people who are potentially at risk of eviction in the wake and aftershocks and ongoing economic stresses of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Their sobering lead conclusions:

If past trends hold, the upcoming eviction crisis will lead to higher rates of COVID-19 infection, especially as new variants emerge. The scale of this problem exposes fundamental problems in our labor market and social safety net.

In this piece, we show that the eviction threat looms the largest in Black-majority locales, creating the potential to decimate entire neighborhoods.

Entire neighborhoods.

As the three Brookings researchers delve into the studies, the trends, and the impacts – all of which show disproportionate, concentrated effects in majority-black communities and neighborhoods – harrowing details emerge on households headed by women.

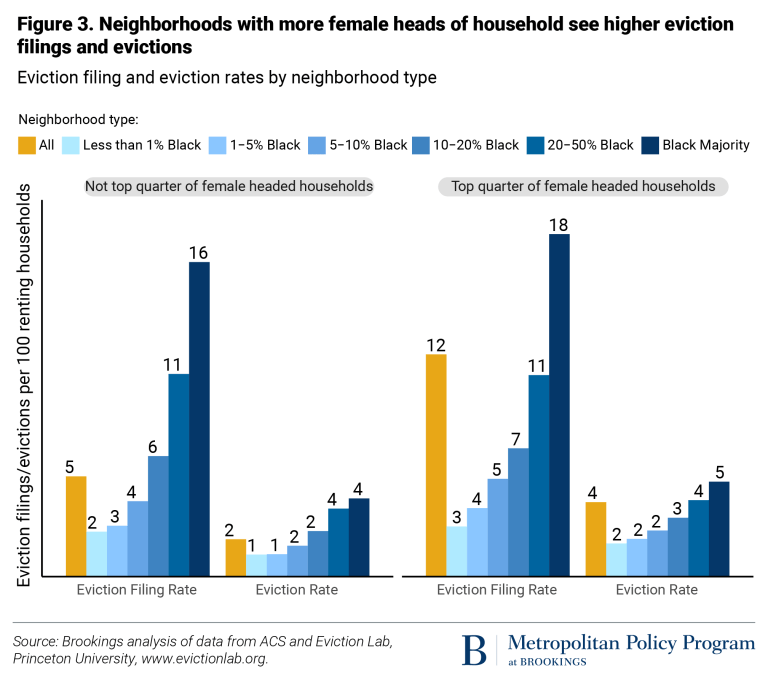

An article from Social Forces found that neighborhoods with a higher number of children and female-headed households experience increased evictions, so we account for the percentage of female heads of household. Eviction filing and eviction rates increased for every neighborhood group in the top quarter of female-headed households.

The Brookings authors recommend six policy strategies that could help prevent high risk of evictions in the wake of the end of the CDC ban from becoming a catastrophe. Two of the five policy strategies speak to every person who regards building, remodeling, planning, investing, manufacturing, developing, etc. homes and communities as a livelihood.

Here they are:

Build more housing. In many cities, zoning laws prevent new housing stock from being added and restrict certain types of housing used by poor people and people of color—specifically, housing that is not single-family housing. Minneapolis changed their restrictive zoning laws just before the pandemic and became the first city to ban single-family zoning, with Berkeley and Sacramento, Calif. following suit this year. While the long-term effects on rent and availability remain to be seen, the reality is that for many cities without zoning reform, the status quo is untenable.

Finally, increase the minimum wage. Evictions disproportionately hit renters with low incomes and those in poverty; nowhere in the country can a single working adult afford a two-bedroom apartment on the minimum wage.

The public sector – at the local, regional, state, or federal level – by itself, can not solve for this, and ward off disaster. Nor can the private sector, by itself, solve for this looming crisis. What does that mean other than it's an "us challenge?"

Join the conversation

MORE IN Policy

California Breaks CEQA Barrier To Reignite Housing Production

Championed aggressively by Gov. Gavin Newsom, the historic environmental law reform unlocks the potential for infill housing—and could become a model for other high-barrier states.

Governor’s Veto Derails Connecticut Upzoning Push

State leaders aim to regroup for a fall special session after a housing bill faces resistance from local zoning defenders.

Can California Clear A Better Path To Housing Stability?

Berkeley’s 8-year “step-up” project exposes the true cost of building even the simplest housing. A test case in transition: When red tape meets a desperate need for shelter.